Pharmaceutical company GSK is on tenterhooks after the Chinese government accused it of being behind a massive corruption scandal.

Pharmaceutical company GSK is on tenterhooks after the Chinese government accused it of being behind a massive corruption scandal.

It is suspected of paying bribes to doctors, hospitals and bureaucrats, among others.

It is not the first time the British company has faced such allegations. In Argentina, the firm was thrust into the public and media spotlight in 2012 due to irregularities in clinical trials carried out to test the pediatric vaccine Synflorix, resulting in the company paying u$s 180 mill in fines. See article. See article.

Pharmabiz commissioned British journalist Joseph Foley to compile an article describing how the media have treated the latest case against GSK at home in the UK.

British media summary by Joseph Foley

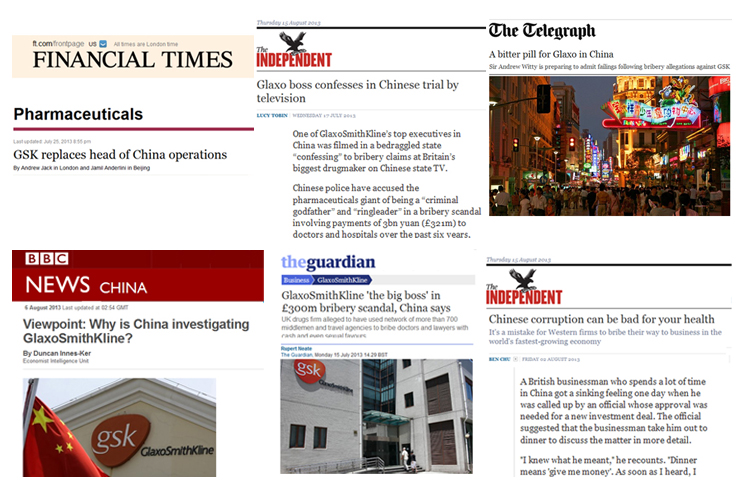

GlaxoSmithKline’s Chinese corruption crisis made waves in the British press, the principal broadsheets following the developments with a mix of scandal and sympathy.

GlaxoSmithKline’s Chinese corruption crisis made waves in the British press, the principal broadsheets following the developments with a mix of scandal and sympathy.

The Telegraph was one of the first to latch on to the story, its Shanghai correspondent Malcolm Moore following developments tenaciously on the Chinese side and recording a rare press briefing by Gao Feng, head of the economic crimes investigation unit at the Ministry of Public Security.

In an article headlined ‘GlaxoSmithKline accused of ‘criminal godfather’ behaviour in China’, Moore detailed the magnitude of the allegations against GSK, accused of handing out more than 3billion yuan (u$s 489 million) in bribes, and pointed out that, the sum would represent a significant proportion of GSK’s annual Chinese sales revenue. See article.

Moore highlighted Gao’s allegations that bribes included sexual favors as well as financial incentives and detailed the mechanism allegedly used, involving 700 middlemen and travel agencies.

Gao said “like a criminal organization, there is always a boss. In this game, GSK is the godfather.”

Moore’s recording was subsequently quoted throughout the mainstream press with The Guardian running the story not only on its business pages but also in a prominent position on its homepage, the most widely read in the UK.

Under the headline ‘GlaxoSmithKline ‘the big boss’ in £300m bribery scandal, China say’, Rupert Neate included a strong defense from GSK, in which the company said it was “deeply disappointed by these serious allegations of fraudulent behavior». See article.

The Independent followed up with the story that GSK vice-president of operations Liang Hong had confessed on Chinese television. Lucy Tobin´s article «Glaxo boss confesses in Chinese trial by television» appeared in the business section of the newspaper. See article.

The Financial Times meanwhile carried the news that GSK had removed of its head of operations in China, under the headline ‘GSK replaces head of China operations’. Reporters Andrew Jack and Jamil Anderlini revealed that Mark Reilly, who had already left China, had been replaced by Hervé Gisserot, one of GSK’s top European managers. See article.

They stressed that Reilly was to “continue to assist in handling the company’s own investigation into the scandal from London”.

Telegraph business reporter Denise Roland, in a comment piece entitled ‘A bitter pill for Glaxo in China’, argued that Glaxo had not known it was under criminal investigation until police stormed its Shanghai offices in June. See article.

She compared the scandal to a tidal wave that “started with just a few ripples”, namely Chinese authorities’ demands for information on pricing practices back in February.

Roland suggested that the real reason GSK had been targeted was that Beijing was desperate to control drug and vaccine prices as it tried to guarantee accessible health care for its entire population.

The BBC’s Duncan Innes-Ker meanwhile, in an analysis headlined simply ‘Why is China investigating GSK?’ argued that China was making an example of GSK not only in an attempt to control its medicine bills but also as part of a general “culture change” in Chinese politics, highlighting the fact that new Chinese leader Xi Jinping had “launched a high-profile campaign against official corruption and extravagance.”

He stressed that foreign companies operating in China needed “to be aware that in the longer run, the grey areas that so many firms operate in will gradually close down as the government enforces better corporate governance.”

The Independent’s economics editor Ben Chu concurred under the headline: ‘Chinese corruption can be bad for your health’. See article.

He argued that corruption was “hard to avoid” in China, pointing out that doctors received low salaries compared to UK standards and looked for ways to supplement their income.

He said the latest clampdown affected local as well as foreign companies but that local companies were better at hiding corruption because they did not have to use middlemen.

After all this, it was with some relief that the press learned that it was not only a British company that was under suspicion in China, The Telegraph picking up the investigation of French firm Sanofi and stressing that other firms were now taking proactive measures.